Everything is an experiment until it has a deadline

"That gives it a destination, context, and a reason.” —Brian Eno

When I was in a more active phase of my writing life—which is to say a more public one, since I write all the time—people would often ask me, at panels and readings, what my writing process was. Behind the question was the idea or hope that somehow the hour you wrote, or the candle you burned, would turn you into a better writer.

I always hated that question, partly because I am not a stellar example of someone who has a disciplined writing habit. I would usually reply by quoting another author who said that the muse only hits when you’re already sitting in your chair, writing. And indeed, discipline is key if you want to eventually get something out of your head and onto the page, much less published. As a book editor, I’ve been frustrated with some short-lived clients who wanted to have written a book, with their photo on the jacket, without having taken the time and work they needed to actually write one. I have parted ways with those clients because I don’t like to try to vacuum books out of people’s brains. Fortunately, I’ve been able to collaborate with some other hard-working authors to midwife their books into existence, learning a lot along the way about their fields. That’s a huge pleasure.

Writing a book takes work, more than most people realize. As for process, many admirable and productive writers get up at the crack of dawn, meditate, make a pot of tea, and then hunker down until a late lunch, after which they take care of their correspondence, shopping, and other bothersome tasks that get in the way of their writing. They get a lot done.

I’m not one of those people, alas. I like to get a lot of sleep and cuddle with my husband in the morning, then eat breakfast, read the “paper,” and do the crossword puzzle with him. By the time I work out and shower, it’s coming up on 11:00. Then I check my emails and, like every other distracted person on the planet, scroll through Instagram. Now it’s almost noon, around the time those 5 a.m. writers are getting ready to pack it in for the day. I usually end up writing in the afternoon. I’m calm and settled by then. That works for me, though I’m not as productive as I’d like to be.

All my early writing experience was as a journalist, so I am trained to write to deadlines. That has often meant last-minute sprints after I’ve procrastinated, actually starting early and jamming until late at night. I have very rarely, in my over 40 years of being a writer, missed a deadline; maybe only once or twice, having to do with illness or emergency. Because I have always written on deadline, I write quickly. This is an advantage for getting things in on time, but not so great for the kind of careful polishing and thought that you need to write something that really sparkles. It’s a bit of a problem for me that even when I write fast, I write well. That is to say, well enough. But if I spent more time on what I wrote, as I sometimes do on pieces that mean a lot to me, they’d be much better. There have been many occasions in my career when I’ve whipped off a pitch to an editor and had it rejected because I wasn’t careful enough. Why I don’t spend more time is a mystery to me. It isn’t arrogance or confidence; it has more to do with fear. What if I was as careful and thoughtful and researched as I could be, and it was still rejected? Then I’d have no easy excuse to fall back on.

But back to process. Writing to deadlines only works when you actually have deadlines. But when you’re working on a longer project, as I’ve been doing now for a few years, there are no actual deadlines. That’s when you have to make up deadlines. This is easier to do for, say, a book project where there is a long deadline, like a year, which you can break up into little chunks and tell yourself that in order to finish, you have to do, say, one chapter every three weeks. But that deadline at the end of the year is still real. If you don’t finish the book, you have to pay back your (long-spent) advance.

The book I’m working on now has no deadline. I’ve written no proposal, I have no agent, no advance, and no contract. I’ve done this on purpose because in the past, I’ve written what I thought an agent or publisher wanted so it would sell. Or rather, I haven’t written what I wanted to write because I was told it wouldn’t sell. Or it’s been some combination of floating a half-assed proposal (see above) to try to get a green light to write. The last time I sent out a proposal, it came back from the one agent I sent it to with the comment that while it was well-written, it had all seemed a little pat, a little too much like stories you tell yourself over and over. I needed to dig in deeper, she said, take more time, interrogate my own stories and conclusions, go on a real quest to understand something I didn’t understand when I started out. That was an excellent rejection.

I once visited my mentor William Zinsser, writing guru and author, among other books, of On Writing Well, in his office in Manhattan (Zinsser was the husband of my father’s first cousin, another excellent writer, Caroline Fraser Zinsser). He asked me what book I was working on, and I told him I wasn’t working on a book because my agent wasn’t keen on any of my ideas, and told me that if I didn’t have another best-seller after An Italian Affair (still in print, two decades years later), it would doom my career. Zinsser was blunt. “That is the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard,” he said. “You’re a writer, so write.” I took his advice, fired my agent (which I regret; I should have just been more clear with her about what I wanted to do) and wrote my next book, All Over the Map, which was a fine book, if not as sexy, but did not sell well. I did not make back the advance. I suppose my career has been somewhat doomed ever since; the last time I saw my second agent, she said, “You’re mid-career and mid-list and there’s nothing I can do for you,” which is not exactly a vote of confidence. I haven’t been hyper-focused on my platform, as you have to be these days, and since I have had to make money, I’ve taken on other kinds of writing and editing to try to make sure I don’t retire in poverty.

But I still take Zinsser’s words to heart. Don’t simply write for approval or for money. Write what you’re passionate about, what you have to write.

Of course I want whatever I write to eventually sell, but here in my 60s, that’s not my main motivation (if making money had been my motivation all along, I’d be a wealthy lawyer or something). I have always been clear about trading financial comfort and security for independence and creativity, something I’ve only been able to do in San Francisco thanks to rent control.

I’m taking a break from other money-making projects now because, these days I have only so much time and energy left. I’m thankfully in excellent health, but I can see old age on the horizon. I have lost a lot of people in my life a lot sooner than I thought they would go. So I’m focusing on writing a book. I’ve told precious few people what the topic of my current project is, because I am sensitive to criticism; one writer friend’s negative comments about my idea shut me down for far too long. I have decided to step away from the publishing machine and write the book I want to write, the way I want to write it. This has been difficult, because holding my cards close means that no one is helping to coach me along. But I’m at the point in my career and life where I need to mainly listen to, and trust, my own advice. It doesn’t mean I won’t eventually be open to feedback and edits, but I want my vision of the book to be fully realized before other people come at it with their sharp red pencils. I want to create a work of art that is strictly and honestly my own.

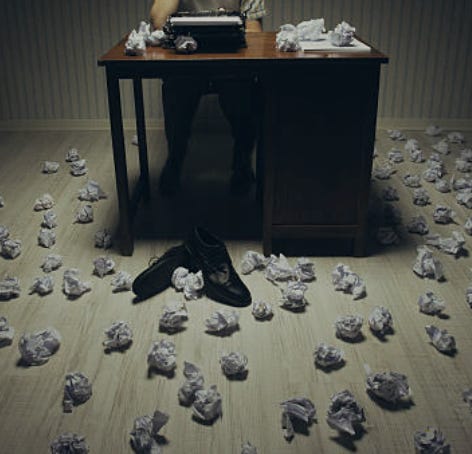

That still leaves me with the problem of deadlines. It’s not that I haven’t been writing; I have about 200,000 words in various documents, some of which I can never find (if you want to talk about process, talk about version control in Scrivener). I’ve written a few scenes over and over, then changed them again. I’ve done things in the past tense and in the present tense, and I’ve mixed them. I’ve succumbed to stupid perfectionism. But recently, I found the right voice and the right way into the material, and I’m on a roll.

So I’m going to give myself a deadline, a year, Oct. 29, 2026, to finish. Maybe I’ll be done before that; I hope so. But it’s not a bad thing to take my time.

And in the meantime, I’m happy to have Substack as an outlet for writing things fast. Thanks for reading. Now, I have a chapter to work on.

Before you go! I’m the program director for the Jacaranda Writing Retreat in Mexico City in March, with three amazing teachers: Xandra Castleton, screenwriting; Jesus Sierra, fiction; and Maw Shein Win, poetry. I’m teaching memoir and personal essay. Come immerse yourself in this vibrant city and in your writing!

Your writing is as beautiful as always even when you write about not writing. I’ve learned so much from you that’s helped me (nearly) come to the finish line for publication of my first nonfiction book in November 2026.

I wrote a blog for 16 years every day with about 5000 dedicated readers monthly.

BUT I never wrote for them. I kind of had a subject when I sat down to write but from day 1 I never expected anyone to read it.

It was a great and freeing adventure! I stopped writing when I felt I had nothing left to say, three years ago when I turned 80!