It shouldn't take a brain surgeon to understand sexism

Remembering Frances Conley, the first tenured brain surgeon in the US, who walked out on Stanford when they refused to promote her after years of sexist slights.

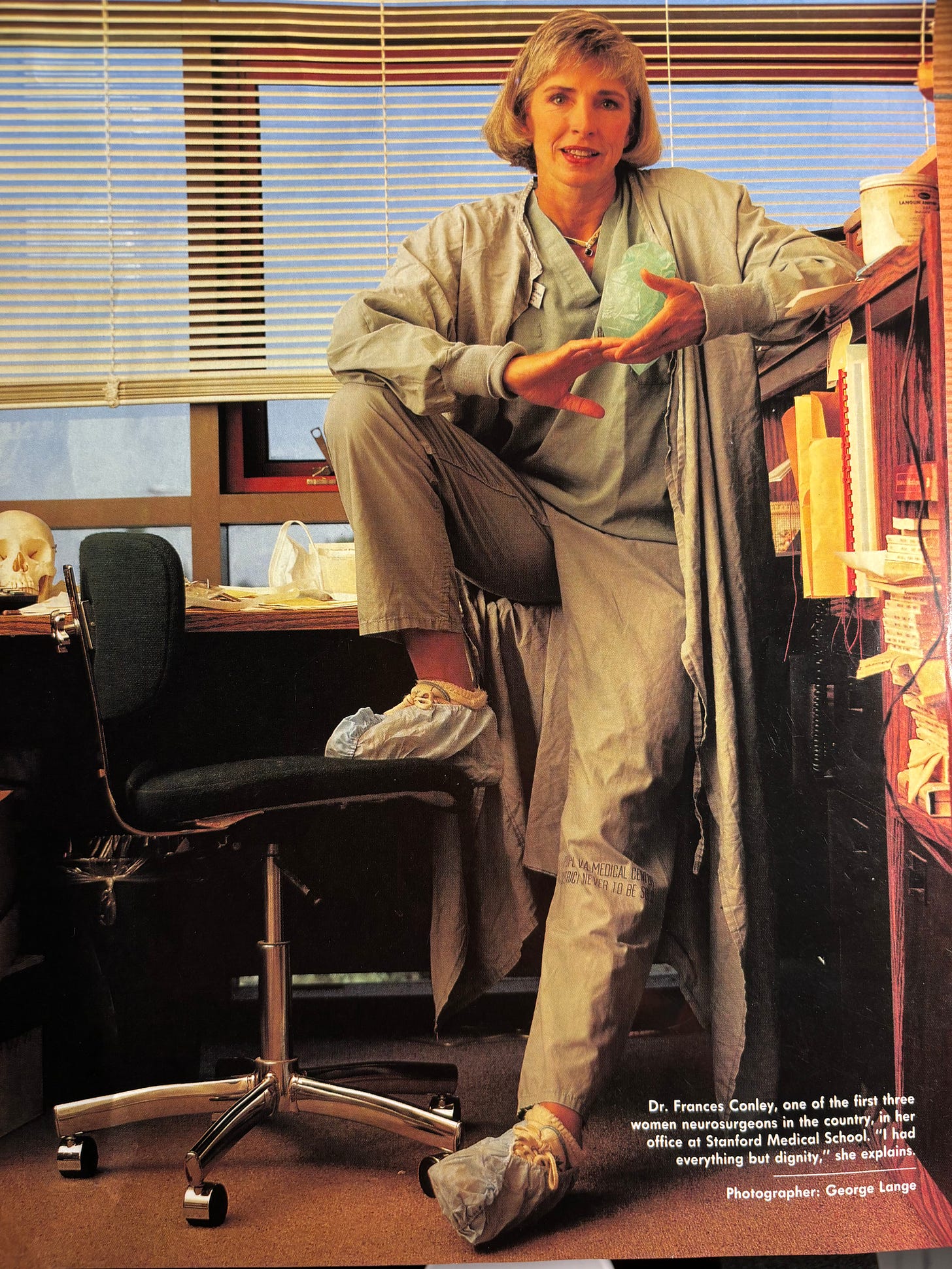

Last week, Frances Conley, the first tenured brain surgeon in the US, died at the age of 83. I had the opportunity to interview her for Vogue 32 years ago, when she was 51. She had just resigned from Stanford Medical School as a tenured professor for being passed over for a promotion that she deserved.

For Conley, it had been the last straw. For 25 years, despite her innovations in the field, her successes at surgery, and her research studying how the immune system could be harnessed to fight brain tumors (way ahead of her time), she was still being degraded daily by her colleagues. They pinched her, called her “hon,” asked her to get coffee, made sexual advances, belittled and ignored her — all towards a person who, if she had been male, would have been treated like a hospital God, with complete respect and even fear.

In 1991, when Conley didn’t get her promotion, she went public, and started a nascent sort of “me too” movement at the time, with hundreds of academics supporting her. Finally, the university backed down, and promoted her to the position she had long worked for and deserved. In 1988, she published Walking Out on the Boys, a memoir of her experiences in the rarefied white male world of neurosurgery.

Conley was a trailblazer in other ways. In 1971, she was the first woman to cross the finish line at the Bay to Breakers race. That was the first year women were allowed to race, but in fact, she had crossed the line the year before, registering as “Francis” and wearing an overcoat to disguise her gender.

I was a young journalist at the time, 30, and despite having done a lot of medical reporting, I was intimidated to interview a brain surgeon. It turned out she was down-to-earth and friendly. She invited me to watch a spinal surgery, which I recall being a lot more like woodshop than how I imagined neurosurgery. Dr. Conley wore running shoes, which were not common for female physicians at the time, and it turned out that she crusaded against high heels because they cause back pain. My only discomfort during the surgery was being pimped by a medical student who thought I was another medical student (which in fact was my cover for being allowed in the OR); he quizzed me on what various body parts we were looking at, but Dr. Conley saved me by giving him a look that quieted him down.

My wonderful editor at the time, Peggy Northrop, encouraged me to take the story further than her experience of sexism and into the realm of “micro-iniquities,” the kinds of subtle slights that women and people of color experience all the time in the workplace, which are sometimes too subtle to fight against, so much so that one could become convinced she was oversensitive or reading into things or just not playing along with the game.

Dr. Conley didn’t play along with the game. She fought back. She ended up at the top of her profession, married to an Olympic javelin-thrower, then retired to Sea Ranch.

All these years later, despite her efforts, female neurosurgeons are still rare; only 8.2% of those practicing in the US. Meanwhile, at Stanford, Dr. Odette Harris, promoted to professor in 2018, is only the second female neurosurgeon after Dr. Conley to attain that position. And the Association of American Medical Colleges reports that nearly one in three women still experience sexual harassment in academic medicine. That’s not even to mention how much of medical training is based on medicine for men.

I wrote this story half my lifetime ago. When I see the kind of depth and space that Vogue let me write, I feel both glad to have been working there for those salad days —I made $2/word and this piece ran something like 3500 words—and sorry that the magazine doesn’t run anything this length, and rarely so in-depth. Nor do many other magazines. Anna Wintour green-lit the piece because it’s an issue she cared about; she’s not responsible for the turn in magazine economics that has devalued journalism and shrunken the pages of even the most robust magazines. But it’s fair to say that a story of this length would never run in Vogue today, which is a shame. What made this story work was the subtlety that can never be conveyed in a 500-word post.

A few years after the piece, a friend of mine, Angus McKenzie, an investigative reporter, found out that he had a deadly brain tumor. When he told me that Dr. Conley was his surgeon, I felt reassured that he was in the best of hands, and she likely extended his life for several months. I feel honored to have known Dr. Conley and written about her.

Excellent writing. Thanks for sharing