The revolutionary I Hate to Cook Book

Why Peg Bracken's cheeky cookbook may have been as influential as Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique

I am visiting my 95-year-old dad in Colorado, in the senior residence where he and my mother moved in 2011. Over dinner with a friend of hers, I remarked that while my mother only lived in the residence for six months, she enjoyed every moment of it—because she didn’t have to cook.

She’d always hated to cook, and resented that it was part of the ‘60s and ‘70s deal for women. The fact that my father dislikes fish and most vegetables (“rabbit food”) made cooking that much more of a difficult task. At the senior residence, where they got a meal a day, Mom said the thing she loved most was, “I can eat fish every day. And I do.”

For women who’d rather put their hands around a wet martini than a wet flounder

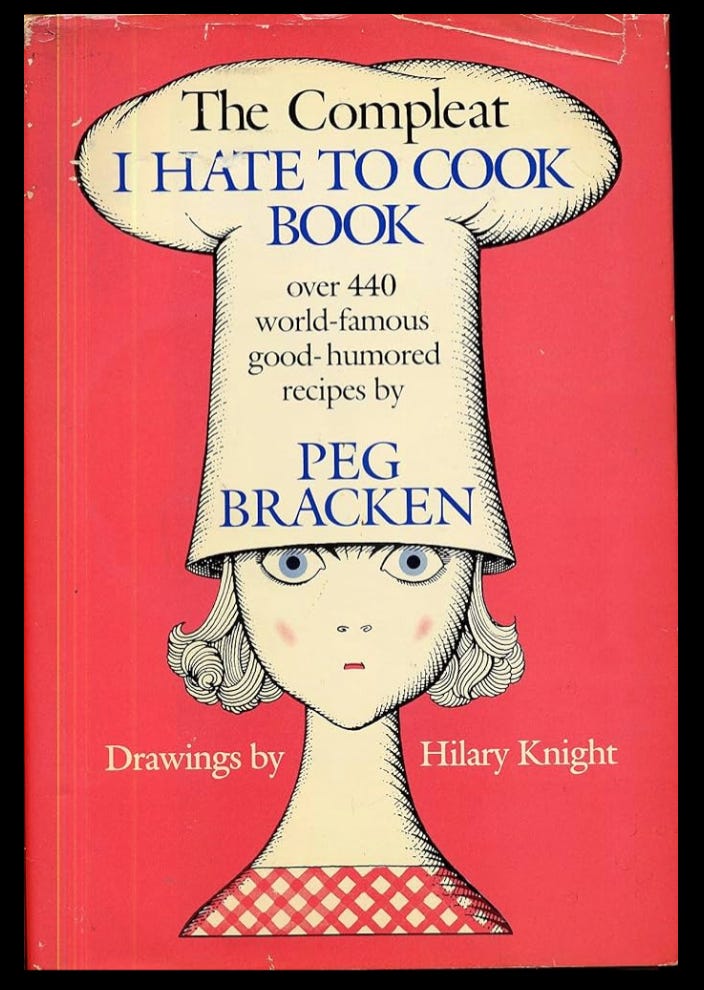

My mother’s favorite cookbook was the I Hate to Cook Book, by Peg Bracken (shelved right next to the Joy of Cooking, whose title Mom considered quite a stretch). In 1960, Bracken breezily defined a big part of what Betty Friedan would characterize, three years later, as the “problem that has no name” in The Feminine Mystique.

The problem, according to Bracken, was simply that if you had to cook, and no one asked you whether you wanted to do it, much less paid you for it—it just came packaged with your diamond ring, along with the diapers and housework—you might very well hate to cook. Sixty years later, it’s hard to imagine, thanks to women like Betty Friedan and PegBracken, what drudgery cooking was then.

Today, I can cheerfully complain about cooking—not being able to find the perfect heirloom tomatoes, fresh mozzarella, or salt-cured capers—because cooking is more of a pleasure than a chore. I have a choice about whether or not I cook, as well as a marvelously efficient sous chef, my husband Peter. I love to cook—imagining the most delicious thing to eat for dinner, going on a quest for ingredients, enjoying the meditative calm that comes with chopping and stirring, seasoning things just right, and savoring the meal with a big helping of self-congratulations.

But if someone told me I had to cook every day—especially food I didn’t particularly like for five ingrates—it would instantly lose its appeal. Expect me to cook and you can expect me to suggest we go out for sushi. It’s only because we don’t have to cook that people like me are free to be the rapturous foodies that we are. Peg Bracken gave women of my mother’s era a choice about cooking—not about whether they had to do it, a question that was not yet on the table, but at least about whether they had to pretend to be happy about it, which was a first step.

Her cheerfully subversive cookbook made it feasible for women like my Mom to stop feeling guilty about not enjoying their wifely role as cook, or not doing it perfectly, and to feel good about wanting to do just about anything else instead.

“This book,” Bracken wrote in her introduction to the I Hate to Cook Book, “is for those of us who hate to [cook], who have learned, through hard experience, that some activities become no less painful through repetition: childbearing, paying taxes, cooking.”

Bracken, an advertising copywriter, pooled the recipes of all her friends who’d rather, as she put it, put their hands around a dry martini than a wet flounder. She copied the easiest of them from “batter-spattered file cards,” added a splash of alcohol to some (along with a glass for the cook), and gave them witty names—“StayabedStew,” “Sole Survivor,” and “Hurry Curry.” The chapter titles—“Company’s Looming,” and “Desserts: people are too fat anyway”—gleefully announced recipes whose main purpose was to get the cook in and out of the kitchen as fast as possible.

The I Hate to Cook Book contained a dash of cheerful resentment about having to cook, which women like my mother loved. “Never compute the number of meals you have to cook and set before the shining little faces of your loved one in the course of a lifetime,” she wrote. “This only staggers the imagination and raises the blood pressure. The way to face the future is to take it as Alcoholics Anonymous does: one day at a time.”

The I Hate to Cook Book made no less an impression on my mother than the Feminine Mystique would a few years later—maybe more. It defined the housewife’s problem with sympathy and wit, and provided some practical and liberating solutions. The tone was positively rebellious: “Add the flour, salt, paprika and mushrooms, stir,” Bracken instructed in her recipe for Skid Road Stroganoff, “and let it cook five minutes while you light a cigarette and stare sullenly at the sink.”

It’s easier to change your friends than your recipes

Bracken cracked the image of the perfect, satisfied, frilly-aproned housewife—and offered her a glass of wine. She disdained the snobbishness of the kind of coiffed suburban wife who ran around pronouncing food names in French and extolling the virtues of another revolutionary of the time, Julia Child. She counseled women to stop trying to impress their guests with difficult canapés, which were over-rated anyway. “By 8:00 they look as though the guests had been walking through them barefoot.” She also eased the kind of panic my mother always experienced for hours before guests arrived, and suggested you don’t need to worry about whether you’ve repeated the dish to your dinner guests, going to such lengths as keeping a notebook of what you served to whom and when.

“If you find you are serving the same thing too often to the same people, then invite someone else instead. It is much easier to change your friends than your recipes.”

Bracken, who died in 2007, also had little tolerance for people who talk about food all the time—tiresome boors like me, who are capable of spending an entire meal reminiscing about a lunch I had in Piemonte, Italy or to planning a future Peruvian-themed dinner party. Food was just food, to be dispatched with in the kitchen and at the table as quickly as possible. “Now once in a while,” Bracken warned, “you'll find your self in a position where you have to talk about cooking. This is usually a sitting-down position with other ladies hemming you in.” Nothing could be worse.

Like my mother Bracken had a rather Puritanical attitude about cooking and food, considering them much more a necessity than a pleasure, best done behind closed doors. “Actually, your cooking is a personal thing, like your sex life,” Bracken wrote, “and it shouldn't be the subject of general conversation.” Bracken’s brand of liberation came as a package: she not only said it was perfectly fine to hate to cook, but offered fail-proof recipes for quick meals, which reduced the sentence of time served in the kitchen. Many of her recipes are stews, which combine all the ingredients of a meal—vegetables, potatoes, meat—in one slow-cooking pot.

Her recipes relied on the convenient, packaged foods that manufacturers had been promoting since just after World War II, printing easy recipes on the sides of the boxes, which women were using but feeling guilty about because it seemed unwifely and unimaginative within their limited creative sphere. But Bracken gave such foods as cream of mushroom soup, frozen spinach, canned green beans, bouillon cubes, Spam, and packages of instant onion soup mix her enthusiastic blessing. In her Beef a la King recipe, she instructs, “Don’t recoil from the odd-sounding combination of ingredients here, because it’s actually very good. Just shut your eyes and go on opening those cans.” It isn’t surprising that after the success of her book, Bracken became a spokesperson for Birds Eye frozen foods.

Mom took the I Hate to Cook Book’s recipes and permission to spend as little time in the kitchen as possible to heart. When someone told her it was fine to take her identity out of the kitchen, she fled. Mom was born to be an activist, not a cook. By high school, I was cooking most of the meals while she was working full-time.

Bracken’s book was initially rejected by five male editors, and by her second husband, Roderick Lull, who commented “it stinks” before becoming her second ex-husband. A female editor commissioned the book, with a $338 advance. It went on to sell three million copies—twice as many as Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking( 1961) and the same as Craig Claiborne’s The New York Times Cookbook (also 1961)--and was reissued recently in a 50th-anniversary edition.

For more dish on women and cooking in the post-war period, read Laura Shapiro’s book, SomethingFrom the Oven: Reinventing Dinner in 1950s America(Penguin, 2005).

My young single mother would have loved this book! Instead, she married a chef.