The Tallest Dwarf, the thinnest fat person

Julie Wyman's film debuts at the SF Film Festival 4/26 & 4/27

I met Julie Wyman about 25 years ago, when I was researching my first book, Losing It: America’s Obsession with Weight and the Industry that Feeds on It. She was among the several fat activists I interviewed, women who were trying to make peace with their bodies that didn’t conform to our narrow cultural standards for what women should look like.

Julie stands with fashion mannequins at Zara. Photo by Tijana Petrovic

Julie, who is now a filmmaker who teaches at UC Davis, was, like me, a kid whose body didn’t fit in, and who was teased from the time she was little. I was slightly overweight, born to parents who magnified that difference and shamed me for it, as did kids at school. Julie was differently-proportioned than other kids, with shorter limbs and a smaller top half than bottom. She, too, was teased, called “Oompa-loompa” by others.

“It’s hard to feel like your body is wrong,” she says in her new documentary, The Tallest Dwarf. “I felt that way as a kid.”

Julie’s work has always focused on people’s whose bodies don’t quite measure up to cultural standards. She takes on body image, the ways the media can magnify our negative body images, and ways personal embodiment—athletics, dance—can change those poor body images.

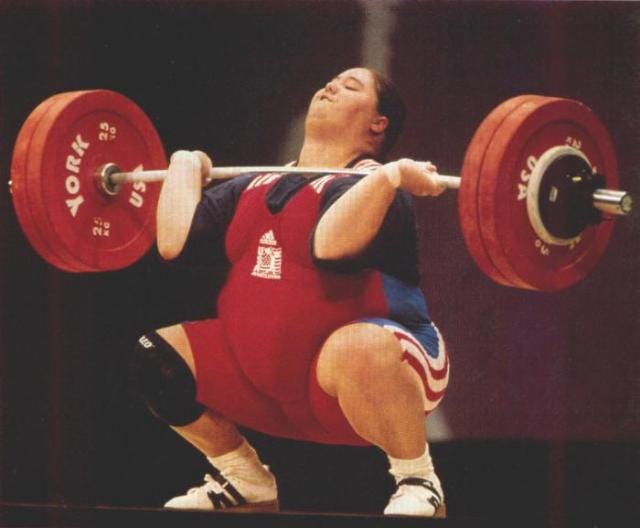

An earlier film, Strong, focused on Olympian Cheryl Haworth, a 5’8” female world-class weightlifting champion who weighed over 300 pounds. It was fascinating to see this elite athlete going from being admired and respected in the small world of weightlifting to being subject to the same fat shaming other plus-size women put up with the minute she stepped out of the gym. Her power and strength and single-focused determination challenged our ideas about size and “will power.”

Cheryl Haworth successfully lifted 354 pounds at the Pan American games in 2005. Lifting that much weight requires having a lot of weight as a base.

In her new film, The Tallest Dwarf, Julie explores the world of small people—she herself is just 5’ tall, which makes her just a few inches too tall for the Little People of America’s limit of 4’ 10”. She grew up suspecting that she and her father, who shares her short-limbed physique and small stature, had some sort of dwarfism. Her parents were never critical of her body. “I just thought you had a great body,” her mom says, allowing that the pediatrician had asked about dwarfism in the family. (Her sister rolled her eyes at what Mom was saying for the camera.)

When genetic testing reveals that Julie does have a rare form of dwarfism—called hypochondroplasia—her father considers, “if we had known this earlier, we might’ve given her drugs.”

The question about what to “do” about dwarfism is a huge one in the community. Julie attends the Little People of America National Conference, where there is a tension between accepting their bodies as they are, even if many have to undergo various surgeries, and taking growth drugs (one Genentech developed quickly grew the biotech industry) or getting limbs elongated.

This is similar to debates within the fat community about whether people should accept that people can be beautiful and healthy and fat, or whether it makes sense to take GLP-1 drugs that can not just help people lose weight, and perhaps make them healthier, but calm the kinds of food cravings that have tormented them all their lives. As with most issues about bodies, it’s highly individual.

Julie. approaches the small people community as both an outsider and an insider. She acknowledges that she is tall for a dwarf, and doesn’t face the kinds of challenges small people face trying to do the most basic things, like sit on a couch or press an elevator button.

The cast of The Tallest Dwarf walks away from their body cut-outs at the National Conference of Little People. Julie, the “tallest dwarf<,” is second from the right. Photo by Gabriella Garcia-Pardo.

I had a similar experience around the time I met Julie, when I went to a National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance conference. I had always felt fat growing up, but at this conference, I was doing the math in the elevator when there were four of us and it had a weight limit of 2000 pounds. I went to the pool party for a swim and wasn’t allowed in because it was a “safe space” for fat people. However much I had internalized a self-image of being fat, being a size 12-14 among people who almost all doubled that size made me an outsider, and them suspicious of me. It was the problem with that book: Some people (like Gina Kolata in her New York Times review) criticized me for writing an expose of the diet industry and culture when I was just “slightly overweight,” and could therefore not have any real insight; others criticized me for writing it to justify my being 20 pounds heavier than an ideal. There was no winning.

Julie manages this insider/outsider status deftly, as she leads a workshop about movement and body image, to “reinvent how we’re seen.” She’s an outsider who nevertheless feels a connection to the community, her people, and she shares her skills and perspectives with the others, without trying to fit in. Using photography and paper cut-outs, she’s able to create new images of people’s sizes. She also tests her proportions and her dads’ against Leonardo da Vinci’s famous depiction of ideal proportions, concluding that they are only about 5% off the ideal.

At the conference, Julie delves into the freak-show stereotypes of little people, and images of them throughout history. “This is a community that is invisible but always on display,” says one woman. No one thinks what it’s like to live with dwarfism, and yet everybody stares.

Cast members Aubrey and Katrina on a scaffold. Photo by Gabriela Garcia-Pardo.

By the end of the film, Julie is, like many of the little people at the conference, beginning to embrace her body more. She realizes that this strain of dwarfism has run through her family tree’s several branches. She even regrets that she didn’t have children, because she has no one to whom she can pass along the trait.

A lot of the peace she—and others at the conference—find with their bodies comes from embodiment, from movement. The film starts with beautiful abstract shots of people dancing, flowing, waving their hands and arms in a way that doesn’t allow you to see their proportions. It is simple, lovely, human movement that says we are all expressing our bodies, and sharing that expression, whatever size or shape they may be.

The Tallest Dwarf screens as part of the San Francisco International Film Festival:

Saturday 4/26 NOON Letterman Premier Theater, SF Presidio (closed-captioned with Audio Description)

Sunday 4/27 NOON at Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley Art Museum (closed-captioned with Audio Description)

Thanks for this piece! I appreciate reading about your parallel experiences of being not ___ "enough" to vocalize concerns about body shaming. It's also didn't know that the term "dwarf" was in use, and now I want to see the film.